I had a busy night on Twitter recently. When the National Review’s David French posted a piece entitled, “Stop Exaggerating the Importance of Donald Trump,” I felt compelled to respond: The essay I wrote after the 2016 election began with the sentence, “It is impossible to exaggerate the significance of Donald Trump’s victory.” So I tweeted something snarky at French, resulting in this exchange:

I spent the rest of the night receiving notifications that people had “liked” Cooke’s and French’s replies to me. My own tweet received a paltry four upvotes. You could say I got dunked on. But the point here isn’t to soothe my ego by revisiting stupid online arguments (That’s what Twitter itself is for). Rather, my point is to ask: Who’s right?

French is not the only sentient person to have suggested that, despite Trump, the world is actually in decent shape — perhaps the best shape it’s ever been in. In a recent column entitled, “What’s Wrong With Radicalism,” David Brooks argued that,

[Radicals] are wrong that our institutions are fundamentally corrupt. Most of our actual social and economic problems are the bad byproducts of fundamentally good trends… Technological innovation has created wonders but displaced millions of workers. The meritocracy has unleashed talent but widened inequality. Immigration has made America more dynamic but weakened national cohesion. Globalization has lifted billions out of poverty but pummeled the working classes in advanced nations.

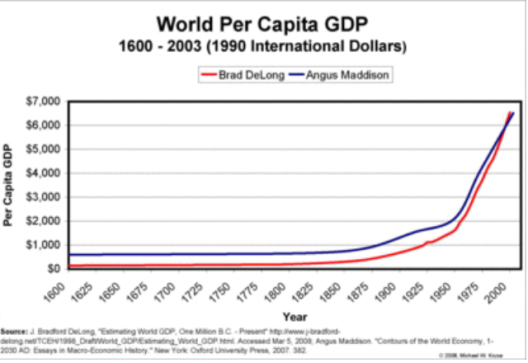

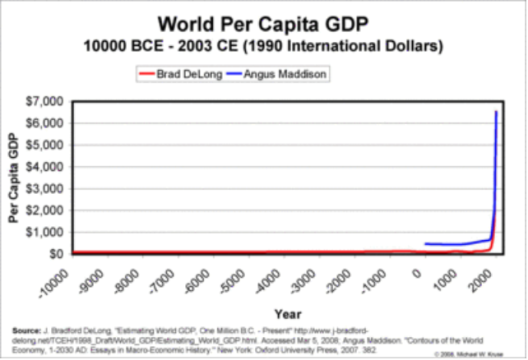

For once, Brooks is right. Today, average person is better off materially than she’s ever been in the past…

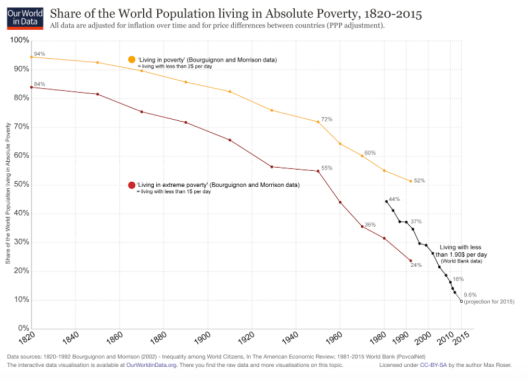

… and fewer people are living in absolute poverty than ever before:

People are living longer, healthier lives than ever before, thanks in part to modern medicine and healthier lifestyles…

…and in part to the decline of violence:

And, Brooks suggests, compared with trends of such world-historical significance — a sixfold increase in per-capita global GDP since 1900, the doubling of life expectancy over that same span, etc. — Donald Trump can’t be that big of a deal, right?

I have a hard time engaging with French’s piece because his perspective is so different from mine (meaning wrong). Things he sees as good, I see as bad. But like Brooks, he seems to argue that Donald Trump isn’t a disaster because he isn’t powerful enough to be a disaster. French argues that larger beneficent forces mitigate Trump’s malignant impulses. Trump is unfit for office, French says, but Republicans have pushed him in the right direction (Gag me). And — more importantly — while Trump displays authoritarian tendencies,

the American political system was built from the ground-up to resist the corrupting or authoritarian impulses of any single president, even unfit presidents. Presidents can do damage, certainly, but their ability to fundamentally transform America absent agreement with two other branches of government and the sustained consent of the American people is nearly nonexistent.

French is right that under our Constitution, Congress and the courts can check a rogue President. He is laughably wrong to suggest that the current Congress has even attempted to do so. And unchecked, even encouraged, by Congress, Trump has set about destroying the traditions of good governance that actually did make America great, and that were largely responsible for the unprecedented peace and prosperity that the world has enjoyed since the end of World War II. The world is indeed in good shape right now, more peaceful and prosperous than it has ever been. But Trump is a cancer eating away at the institutions that made it so.

Let’s step back and ask: Why is the world such a better place now than it was 200 years ago? The answer is: liberalism (In the European, The Economist sense more so than the current American sense). The defining principle of liberalism — whose root, libérer, is French for “to free” — is that if you want to improve people’s lives, you should give them the freedom to do so themselves. Thus, in the political sphere, liberalism means democracy; in the economic sphere it means free markets. The United States was founded on this principle, and from that foothold liberalism has spread throughout the world because it constitutes the best form of social organization that humans have yet discovered.

I’m not going to try and marshall a full intellectual case for liberalism right now. To be honest, it is something of a faith — admittedly an easy one for a rich white man to hold (Just let people, including me, do what they want!). But it seems to me that history has borne out that faith, and in a few broad strokes, one can begin to see why.

Liberalism presumes that people are selfish but not malicious, that we generally look out for ourselves but don’t go out of our way to harm others (This presumption finds strong support in evolutionary psychology). People can therefore have convergent interests in mutually beneficial rules of social order: Everyone will support a law that benefits everyone. Crucially, liberalism proposes that social life doesn’t have to be a zero-sum game; rather, there are rules to live by that leave everyone better off than without them. (The point of John Rawls’ “veil of ignorance” is in part to encourage people to think about such rules.) Often, these rules are ways to escape the collective action problem or prisoner’s dilemma — situations in which, because people’s actions affect not just themselves but others, everyone following their own incentives leaves everyone worse off than if they restrained themselves. Property laws, for example, work to the benefit of all by incentivizing people to use their labor to create tradeable valuable; without property laws, no one would make anything, for fear of having it stolen. As David Hume argued in his Treatise of Human Nature, “it will be for my interest to leave another in the possession of his goods, provided he will act in the same manner with regard to me.” Another classic example of a mutually beneficial rule is pollution control: A rule forcing people to limit their pollution will leave everyone better off than if everyone polluted as much as they wanted.

Democracy is a linchpin of liberalism not because it respects some metaphysical “natural rights,” but because it is the best way to find and enforce social rules that generate the greatest good. Because people are selfish but not malicious, the more people a law benefits, the more people will support it; thus, democratic politicians who want to gain power must propose laws that benefit as many people as possible (A weaker version of this principle is that, while people might not know what’s good for them, they can at least tell when they’re getting screwed. The unpopularity of the GOP’s efforts to repeal Obamacare and cut taxes for the rich aptly demonstrate this principle. Empirically, one of the most important ways that democracy promotes overall well-being is by allowing people to punish politicians who serve themselves rather than the public: established democracies are less corrupt than other forms of government.) Civil rights — free speech, free press, voting rights — further promote the general welfare by ensuring that all people can participate in the political process and have their interests represented. Civil rights thus push democratic governments away from exploitative, zero-sum policies, wherein a group in power exploits powerless minorities, and towards mutually beneficial ones that serve the interests of all (Civil rights and the right to participate in politics generally distinguish “liberal democracy,” which respects them, from pure majoritarian democracy, which may not. Take, for example, Turkey or Hungary, where opponents of the government are badgered into leaving the public square.)

Moreover, liberal democracies have an interest in seeing liberal democracy expand, because liberal democracies get along with each other. First of all, liberal states offer each other opportunities for mutually beneficial trade: Two countries can each specialize in producing what they produce best and then trade with each other, leaving both sides better off than if they had to produce everything themselves. Second of all, as Immanuel Kant predicted back in the 18th century, democracies almost never go to war with each other, because war turns a trading partner into an enemy, and because voters don’t want to go die in foxholes (or pay someone else to go die in a foxhole for them). Historically, wars have generally been fought for the benefit of elites rather than average people, and when average people get a say in the decision, war becomes less likely. Think about 18th century Europe: While kings, emperors and dukes repeatedly plunged the continent into war, England — at the time the only quasi-democracy in Europe, save ever-neutral Switzerland — often stayed back rather than fight to exhaustion, because voters didn’t want to finance the war.

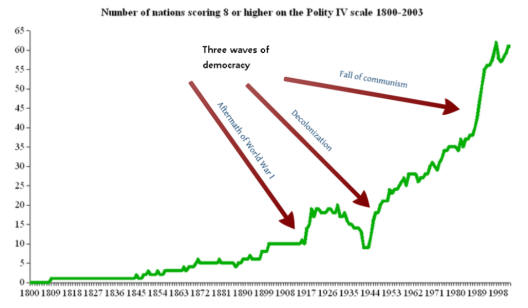

So liberalism makes for good domestic policy, and it tends to spread, both because liberal states want it to spread and because people living under illiberal governments want it to spread. And if you compare the remarkable social progress of the past 150 years to the spread of political and economic liberalism over that same time, you can see a trend:

As democracy spreads…

…and trade expands…

… violence declines…

… and the lot of the average person improves…

… by a staggering amount in a remarkably short time:

Like I said, I’m not trying to put together an airtight intellectual case for liberalism (a bunch of graphs with similar slopes is generally not accepted as proof of causation, particularly when discussing complex social systems encompassing billions of people). But the way these graphs track each other — and other related moments in the spread of liberalism, like the Bretton Woods agreement and the GATT in the 1940s, which created modern the framework for international trade — suggests that such a case can be made.

So where does our current President fit into all of this? Right smack-dab in the fucking middle.

The United States gave liberalism its foothold in the world. When the Constitution was ratified and the United States was created, it was perhaps the most radical political act the world had ever seen, a dramatic inversion of the traditional idea that sovereign governments were ordained by god, and citizens had a moral duty to obey them. Although American identity has always been strongly Christian, the Constitution, with its bold protections for religious liberty and its immortal opening words, suggested a different sovereign than God: “We the people…”. As the American philosopher Richard Rorty writes of John Dewey and Walt Whitman, two of the foremost proponents of this secular American identity:

In the past, most of the stories that have incited nations to projects of self-improvement have been stories about their obligations to one or more gods… [Dewey and Whitman] wanted Americans to take pride in what America might, all by itself and by its own lights, make of itself, rather than in America’s obedience to any authority—even the authority of God.

All too often, the United States has fallen short of Dewey and Whitman’s hopes for a country dedicated to freedom. Our country was founded on slavery and genocide; throughout the Cold War we toppled democratic governments in favor of repressive oligarchs; in Vietnam, Iraq, and a dozen other pointless and evil wars, we have killed millions of innocent people for no reason at all. But despite this, the United States is the main reason that since 1787, the world has become more free, and thus more peaceful and more prosperous.

Since the founding, by example and by policy, the United States has encouraged the spread of freedom throughout the world. The American Revolution helped inspire the French Revolution, which in turn helped inspire the revolutions of 1848 and the spread of democracy in Europe; after World War I, the United States pushed for “peace without victory” and the League of Nations; when these failed and World War II came, the United States helped defeat Nazi Germany and imperial Japan and saved Western Europe from totalitarian communism. After the war, the United States created the UN and the framework for international trade, and rebuilt its two enemies, Germany and Japan, in its own image; they are now two of the most prosperous and powerful countries in the world. China’s explosive economic growth, which has lifted hundreds of millions of people from poverty into the middle class, began after it turned away from Maoism — under which millions starved because the government ordered them to melt their farm equipment to make steel — and towards capitalism. In the Cold War, the United States defeated communism not on the battlefield, where our misadventures in Vietnam and elsewhere probably hurt our cause more than they helped, but in the eyes of communism’s own subjects, who saw that the free world offered a better life. Up until recently, Cuban television had to broadcast American baseball games on a delay, so that censors could edit out the at-bats of Cuban-born players who had defected to the United States.

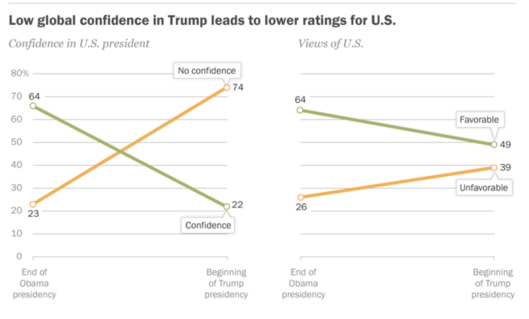

The United States has encouraged the spread of freedom in more subtle ways as well. American politicians and diplomats pester foreign autocrats about respecting human rights. American government agencies and NGOs educate foreign activists, mediate foreign political disputes, and report on government abuses. American trade deals, negotiated by American officials who must take their constituents’ interests into account, require other countries to adopt labor and environmental standards so that foreign companies don’t undercut American ones solely through polluting and exploiting their workers. And perhaps most importantly, simply by existing, the United States provides an example that people stepped on by repressive governments can look to for inspiration. While Americans generally delude themselves about our country’s record on the international stage, we are right to be proud that the world is a more free place because of our influence. And while this would surprise some, the rest of the world appears to appreciate that influence: As of 2013, Pew polls showed that foreigners held strikingly positive views of the United States. (To the people who, not without reason, think the above paragraph is insufferable drivel: If the United States is as evil as you say, then how and why has its rising power coincided with the spread of democracy and wealth around the world?)

Since January, though, world opinion has soured on the United States. Donald Trump has turned being American from a point of pride to one of embarrassment:

These ratings are well deserved, because Trump seems bent on destroying the liberal traditions that have improved the world so drastically over the past 150 years and that were thus responsible for the United States’ previously high standing in the world. Liberal democracy requires a common set of rules and institutions, social constructs passed down through and upheld as tradition. Trump has done his best to upend all of them. He attacks the free press, to the delight of authoritarians worldwide, smearing their accurate stories as “fake news”; he lies constantly, and this “ontological warfare” undermines the mutual commitment to truth that must undergird democracy, in which citizens must understand what their government is doing if they are to retain the ability to control it (Hannah Arendt wrote that, “The ideal subject of totalitarian rule is not the convinced Nazi or the convinced Communist, but people for whom the distinction between fact and fiction… and the distinction between true and false… no longer exist.” This idea was also key to George Orwell’s 1984.) Trump attacks his enemies savagely and personally and threatens to jail his political rivals, making a mockery of the ideal that politics should be a dignified and open activity in which all can participate. He hosts parties at Mar-A-Lago where guests can pay $100,000 to rub shoulders with the President and bend his ear in whatever direction suits them. He treats the rule of law as a nuisance to be coped with when necessary and subverted when possible, rather than as a principle to uphold. While Trump hasn’t brought domestic and international order crashing down quite yet, the norms of liberal politics on which the United States and the international order were founded are anathema to him, and his presidency is damaging them severely, with the tacit approval of the rest of the Republican Party (whose dark-of-night overhaul of the tax code would, in any other world, be the gold standard for violations democratic norms). These violations matter because liberalism does not automatically sustain itself; rather, and paradoxically given its spread around the globe, sustaining it is hard, because liberalism requires us to find a way to live with people with whom we (for the time being) disagree about how to live with people. And being social constructs, the norms that sustain liberalism exist only so long as we continue to uphold them. So while the severity of the damage Trump has done is hard to assess at present, I think I speak for many when I say, I fear we’ll be feeling the aftereffects of the Trump presidency for a long time.

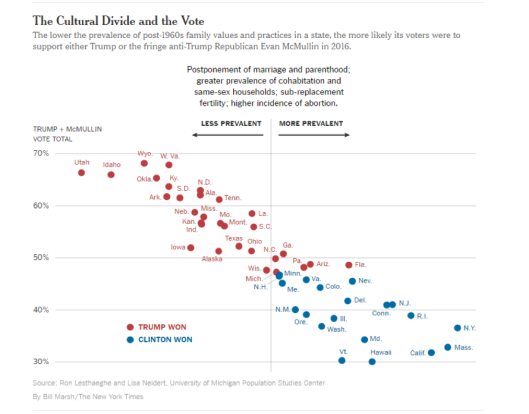

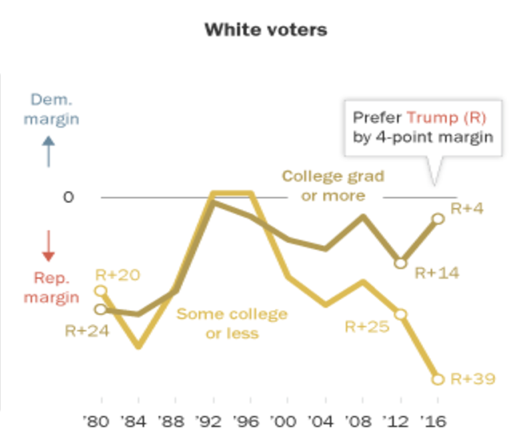

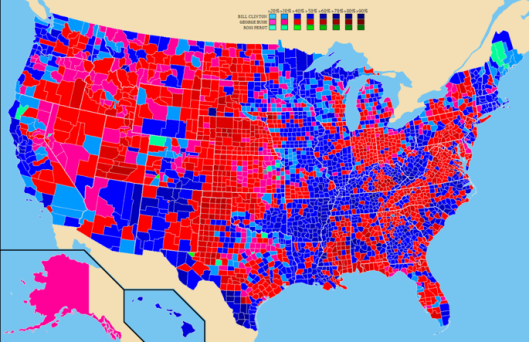

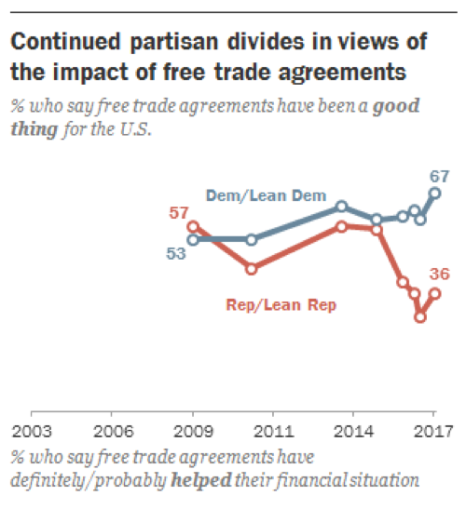

Which makes sense given that Trump’s candidacy was part of a wider, semi-conscious revolt against the international liberal order, a revolt that can’t be entirely dismissed as mindless reactionary backlash. The liberal order had problems, chief among them a lack of equity and the dissolution of national identity. Combine those two and you have Trump, Brexit, AfD and Marine Le Pen, all of which present a toxic mix of economic discontent and ethno-nationalist ressentiment.

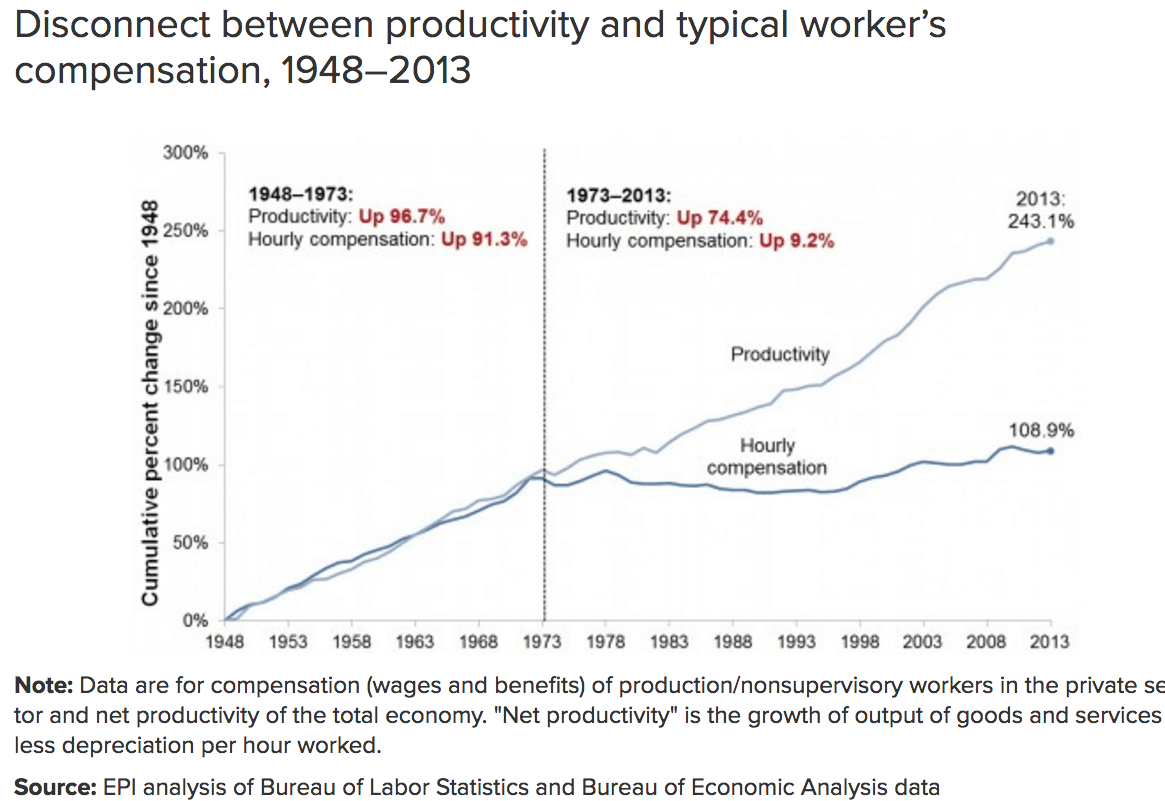

How to generate a toxic mix of economic discontent and ethno-nationalist ressentiment, fig. 1.

But this nationalist backlash against the liberal order proposes cures that are worse than the disease: While globalization has been rough on the middle class of the rich world, it has been much better for everyone else (a provincialist blind spot for the Bernie Sanders crowd, who decry free trade as bad for workers everywhere). The liberal order, for all its problems, has been too successful to be now dismissed as yet another passing historical phase. Rather, the United States should stand up, at home and abroad, for the system it helped create and spread. In practice, that means the Democratic Party must stand up for liberalism at home and abroad, because the Republican Party sold what little soul it had left when it accepted Donald Trump’s candidacy and presidency. This is actually an opportunity for the Democrats, who should portray Trump as an international embarrassment unworthy of his office and of the proud history it carries. Patriotic Americans proud of their country’s previous role in international politics should be receptive to that message. Some of the strongest moments from the 2016 Democratic National Convention came when the Democrats embraced American exceptionalism and celebrated what makes our country great and unique. As Vox noted at the time: “Democrats have stolen the GOP’s rhetoric – and Republicans have noticed.”

But perhaps liberalism is just another passing historical phase; everything else thus far has been. Maybe it’s hubris to declare that no, this time really is different. Maybe people are too scared of death and thus of each other to live under a system that treats all their dogmas as equally fallible. Maybe the relative peace of the past 70 years is due not to politicians giving grandiose speeches at the UN but to mutual fear of nuclear destruction. Maybe notions of freedom and democracy are just a glossy cover for capitalist domination and exploitation that will eventually destroy itself. But I don’t think so, and I hope not, as do smart political writers with whom I agree and disagree. Just look at the graphs: This time really is different. But that doesn’t mean it will last forever. Nothing does.